Holistic approach to maths adds up

January 20 2020

A recent Nuffield Foundation study showed one in ten children between the ages of 8 and 13 suffered from ‘maths anxiety’ and felt either rage or despair towards the subject, leading the researchers behind the report to urge schools to address the issue seriously.

In response, the Sunday Times national newspaper dedicated a section of its annual supplement ‘Scottish Independent Schools Guide’ to shedding light on how the sector is tackling maths in the classroom to ease the UK’s maths crisis. Published over the weekend, Edinburgh Steiner School’s child-led pedagogy was voiced in the article ‘Doing a number on maths’.

For eighty years, our school has been delivering an important alternative to mainstream independent education in Scotland that is rooted in the internationally recognised principles of educational philosopher, Rudolf Steiner – a holistic approach Curriculum for Excellence is striving to achieve. The understanding is of learning as a process. This is truer in the arena of mathematics than in any other subject mastered during a Steiner school journey. It underpins the pupils’ study of the subject at examination level, where every secondary-aged pupil is encouraged to take maths. And they are achieving results far exceeding the national average.

Over half of Upper School pupils achieve an A-grade in Mathematics (51.7%), compared to less than a third (30.8%) Scotland-wide, a review of awards at National 5 over the past 4 years show. Attainment in Maths averages 84% (A-C) over 2016-19. The national average is just 64.4% in the same 4-year period. It is worth noting, pupils are not selected on academic grounds at any stage, and as such there is no entrance exam, and yet our exam results compare favourably with other independent schools in Scotland. Edinburgh Steiner School is listed in the Top Scottish Schools doing Highers for 2019, compiled by Best Schools. These positions are compiled from the % of A grades scored at Highers. These results show the child-led approach is a valid way of working with children to ensure maths anxiety does not endanger learning.

“Mathematics in the Waldorf School is divided into three stages. In the first stage, which covers the first five classes, mathematics is developed as an activity intimately connected to the life process of the child, and progresses from the internal towards the external. In the second stage, covering Classes 6-8 the main emphasis is on the practical…The ninth year onwards is characterized by a transfer towards a rational point of view’ thus writes H Von Barravalle, the first mathematics teacher at the founding Steiner school in Stuttgart for the workers of the Waldorf-Astoria cigarette factory in 1919.

100 years on, many of our pupils who begin school transition from Kindergarten, where the children are in groups of mixed ages from 3.5 – 6.5 years old. Preceding the ages of 8-13, this Early Years unhurried setting integrates mathematical concepts throughout the daily activities. Baking bread or preparing soup from fresh vegetables, and setting the table, involves weighing, measuring, counting, number work and quantity. In watercolour painting, repeated patterns, shape and use of space are discovered. Drawing explores pattern, mark and number making (e.g. a birthday card with candles and numbers), as well as sorting crayons. Sewing offers the child the experience of counting, measuring, ordering and sequencing. Woodwork lets them problem solve, measure, count and use numbers in a variety of ways. Role play employs their curiosity and observation, where numbers are introduced in a variety of ways: Tidying enhances their skills in sorting, counting and sequencing.

To develop a curiosity for learning, maths needs to take practice of different kinds, not only in sitting at a desk with a piece of paper. Scotland is one of the few European countries where children start school aged only four. In a Steiner setting, this formal learning begins in the August after a child’s sixth birthday, when the Kindergarten ‘bigs’ transition to Class 1 (equivalent to P2 or P3 for January/February children); and even then, much of the learning happens away from their wooden desks, and even the classroom.

On campus, an 8-year-old acts out the part of Minus Gnome from the story told by the teacher; aged 11, pupils are given £1 to start a fundraising business project, writing a business plan and selling the handmade items on a stall at the Friday Market; at 13, pupils sculpt a hexagon in clay, deepening their work on geometric solids.

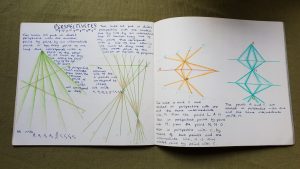

In the Upper School, pupils are stimulated to find formulae and ways of working through problem solving as opposed to learning a formula and getting shown how to work it. They undertake projects in which they meet mathematics in the reality first through problem solving, before abstracting the findings into mathematic generalizations e.g. weights are spring-hung, extensions are measured, and the observed findings lead pupils to straight-line formula.

The Main Lesson Programme – the cornerstone of a Steiner education, stretching right through a pupil’s twelve year school career – also includes mathematics in various forms, including Geometry, Money Percentage, Platonic Solids, Trigonometry and Economics to name a few (Lower School Curriculum – Main Lessons distinguished by block capitals / Upper School). As a result, irrespective of whether pupils veer towards the arts or the sciences in their exam choices, they continue to receive a valuable grounding across all subjects. This broad curriculum was acknowledged in the Sunday Times‘ article ‘Bring the curtain down on career blues‘ (published January 19th, 2020).

The Main Lesson Programme – the cornerstone of a Steiner education, stretching right through a pupil’s twelve year school career – also includes mathematics in various forms, including Geometry, Money Percentage, Platonic Solids, Trigonometry and Economics to name a few (Lower School Curriculum – Main Lessons distinguished by block capitals / Upper School). As a result, irrespective of whether pupils veer towards the arts or the sciences in their exam choices, they continue to receive a valuable grounding across all subjects. This broad curriculum was acknowledged in the Sunday Times‘ article ‘Bring the curtain down on career blues‘ (published January 19th, 2020).

The education lays the foundation for each individual to experience the internalisation of mathematical thinking, teaching the whole child: heart, hands and head or emotional and practical, as well as academic. There’s plenty of time for sitting still and practising arithmetic and maths. But the time spent at a desk is made lively on the inside by the memory of the stories, the games, the movement and the creative activities that make mathematics understood and alive, active, memorable.

As a result, Steiner pupils acquire a deep mathematical understanding that they carry into the exam room.

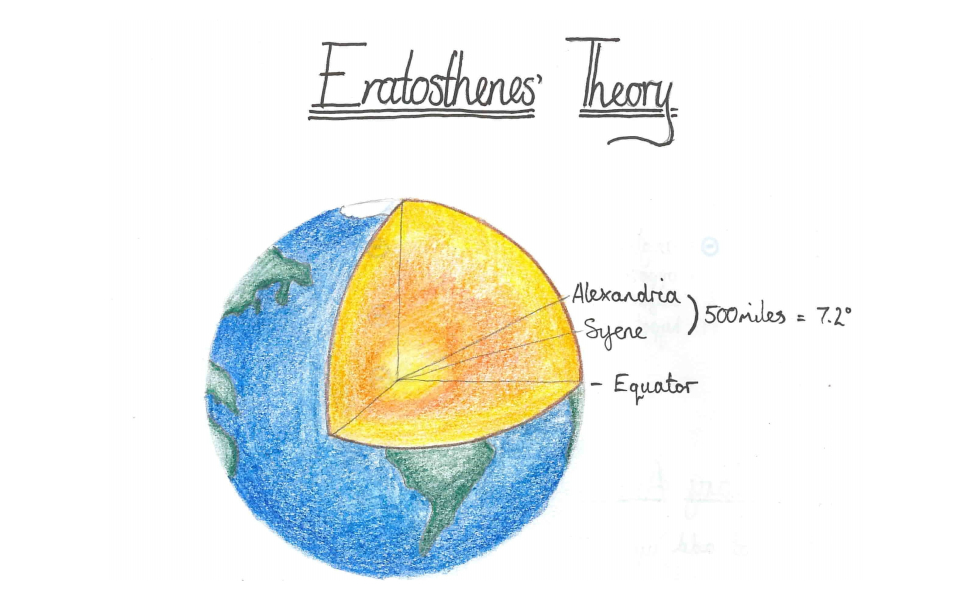

The lesson about Eratosthenes’ findings is an example of teaching through the heart, as the lesson gets wrapped up in Eratosthenes’ biography. This, together with the example of the project on weight-hung spring extensions and the encouragement of pupils to discover the mathematical rules constituting the exam curriculum, gives the threefold aspect (hands, heart, head) of the maths teaching in the Upper School.